Seeing Beyond the Labels: Humanizing the Cancer Experience

If you were to visit the social media page of a cancer patient who openly shares their diagnosis, I’m willing to bet $5 that their comment section would resemble something like this: “You are so brave!”; “You are so strong!”; “You are an inspiration!”; “You are a warrior!” Seemingly well-meaning comments that end up feeling less like compliments and more like expectations.

When I went public with my diagnosis, I automatically felt like an invisible crown was set atop my head, and it was heavy. It didn’t matter who I was before cancer. I was now the poster child of strength and bravery, simply because I was trying not to die. People I hadn’t heard from in years suddenly reached out, showering me with compliments. Somehow, I had become deserving of their admiration, whereas just a week earlier, I hadn’t been. It felt confusing and unnatural, but above all, it felt isolating.

The cancer community has become closely intertwined with battle language, using terms like “fight” and “warrior,” just as we commonly hear “chemotherapy” and “tumor.” I want to make it clear that I will never label those who find comfort in such terms as “wrong.” However, I’m here to present my alternative viewpoint— a perspective that became increasingly apparent to me within a week or two of my diagnosis, and grew even stronger as I navigated through my cancer experience. Notice that I intentionally avoided using the word “journey.” It’s another term that has never resonated with me. If I were embarking on a journey, I would prefer it to be a fun one, certainly not leading me to a place called “Cancer Land.”

Whenever I broach this topic, I often encounter the counterargument that people “mean well.” It’s possible that they simply don’t know what to say, so they believe using these terms is empowering. However, this language made me feel cornered and trapped. I was grappling with my mental health and yearned to be genuine with others. Yet, every time I mustered the courage to express my truth, I was met with toxic positivity or labels. I became fearful of letting people down. Just imagine, you’re on the verge of confiding in someone that you’re struggling, but before you can speak, they call you an inspiration and exclaim, “You’ve got this!” Suddenly, it no longer feels safe to be authentic. The weight of that invisible crown feels even more burdensome, and a knot tightens in your throat.

The feeling of being unsafe permeated my entire cancer experience. When I completed my first 12 rounds of chemotherapy (before my cancer later relapsed), I found myself transformed into a mere shadow of who I once was. And in many ways, this transformation was undeniably real, pushing me further into a state of fight or flight. The “fight” was supposedly over, so why didn’t I feel any better? In a desperate attempt to rediscover my pre-cancer self, I ran full speed back toward the life I had before, returning to work a mere six weeks after finishing chemotherapy. I yearned to reconnect with the woman I was prior to being labeled as “that girl with cancer.” I longed to find the person whose worth was not defined by physical health, but rather by their moral character and their heart. I longed to find my identity again.

On my first day back at work, a co-worker approached me and revealed, with unsettling clarity, how the world now perceived me. They asserted that I should “grasp what truly matters in life now.” That comment slithered toward me like a judgmental snake hidden in the grass. It made me wonder if perhaps the person I used to be wasn’t who I truly desired to become, or maybe she never even existed? They also told me I was “fortunate to be alive.” Oddly enough, I still didn’t feel anything resembling “fortunate,” except that I was indeed not dead yet. Another co-worker shared their own experience with cancer, except it wasn’t a full-blown diagnosis, but rather a cancer scare. While I was genuinely glad they were healthy, I couldn’t help but feel an urge to scream. Why couldn’t I have a story of a “cancer scare” rather than a life that had transformed into one colossal nightmare of a story?

Eventually, I began to sense that many people were using me as a reference point to appreciate their own lives. “It could be worse, look at her.” They felt more grateful for what they had because they compared themselves to my situation. I felt like a cautionary tale, as if nobody cared about my feelings unless they fit the narrative of a heartwarming cancer movie. I guess I couldn’t entirely blame them. I didn’t want to exist in this place either. But damn … it was lonely.

I longed to be everything that everyone had been telling me I was for the past six months, but the truth was, I was broken. So broken that I couldn’t fathom how I would ever pick up the pieces. The fragments weren’t just scattered on the floor; some had been carelessly blown away by the wind, scattered like debris after a tornado. Cancer was the tornado, and I felt like the helpless cow spinning around for cinematic effect. My life had become the movie, and I was just the “poor cancer patient” held up for sympathy. Having expressed my perspective, I believe it’s only fair that I offer some guidance on what would have been helpful to hear in those dark moments. Most of what one says to someone facing a beast like cancer doesn’t need to be overthought or intellectualized. You don’t need to be a celebrity publicist, carefully crafting the perfect response for the world. You need to respond from the heart, from a place of authenticity. Sometimes, it can be as simple yet powerful as saying, “I love you” or “I care about you.” These are the things that the soul craves during such turbulent times. They don’t assign me a role, they don’t impose expectations, and they leave room for my feelings.

Another effective and much-needed response can be as straightforward as saying, “I’m sorry. I don’t know what to say.” It’s OK not to know what to say. I don’t know what to say either. Yesterday, I was Chelsey, and today I am reduced to a mere medical reference number. How can one adequately convey the impact of such a drastic change? Should you even try? Empathy and love can manifest in many forms, and honesty is one of them. I respect someone who acknowledges their lack of understanding but is willing to learn. As newly diagnosed patients, we are learning day by day, hour by hour, minute by minute. I would much rather have someone by my side who is willing to learn with me, rather than acting like they are already an expert, and I should be too.

I know some readers may think, “If people are so particular about terms and expectations, maybe I should say nothing at all.” The worst thing you can do to someone with cancer is to say nothing. Silence.

Some of the most profound grief in my cancer experience came from those who ran away from me as if I were a monster. In a matter of weeks, I ceased being seen as who I truly was. I was reduced to just being cancer. I no longer mattered to some people for various reasons. The reasons don’t truly matter to me anymore. It’s difficult for me to imagine ever forgiving those who made that choice.

So, if all you know how to say is that I’m a “warrior” or “brave” . . . I would still prefer that to silence. At least it shows me that you care. It demonstrates that you are trying.

All cancer patients desire is for you to hold space for them. Space for authenticity. Allow us to be real with you, whether it’s good, bad, or somewhere in between. Even if you find me inspiring, please make sure it’s because of my character or my heart, not solely because of my illness. I am not defined by my cancer; I am Chelsey.

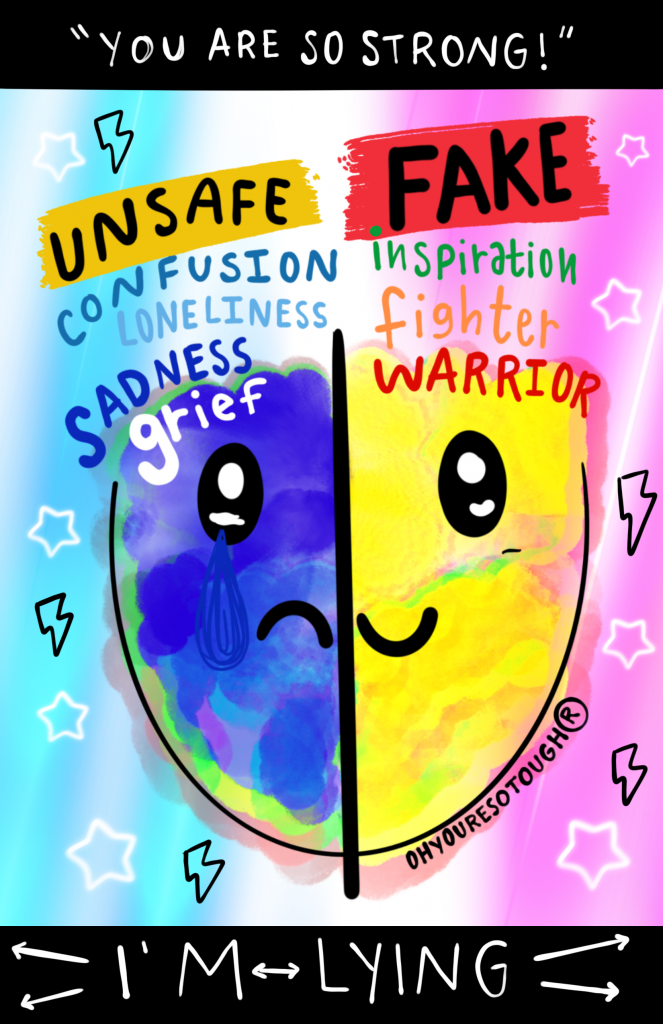

This piece is entitled, “Two Sides to Every Story.” It illustrates the two halves of my identity as a cancer patient when I was going through cancer the first time. On the “fake” side there is a happy face adorned with the labels I was given. Labels that I didn’t identify with, but somehow was supposed to live up to. On the “unsafe” side are terms that illustrate how I really felt inside. However, I wasn’t safe to share those with the world because it didn’t live up to their expectations of me. I wasn’t strong, I was struggling. I felt like I couldn’t share that with anyone until my cancer relapsed. When it relapsed I decided to express my emotions authentically no matter what others thought. I was so tired of hiding and playing a role. I just wanted to be me.

Leave a comment below. Remember to keep it positive!

Dear Chelsey,

Thank you so much for writing this essay. Everything resonated with me. I was diagnosed with thyroid cancer and though now in remission, these comments / being a reference point to others never stops.

I wish you a lot of love and peace <3

Love,

Priyanka